Ka moolelo o kauaʻi – The Story of Kauaʻi

Introduction

IntroductioN: Learn more

The birth of an island, migration of species that become unique due to the isolation of the land mass, people who arrive in tiny sailing canoes and meet and match every challenge, continuing waves of migrating people, warriors, battles, blood, sacrifice, plunder, kings and queens.

It’s a story that’s neatly tucked into the volumes, videos and files of letters, maps, deeds, drawings and photos at the Kauaʻi Historical Society where you can take a step back in time for a taste of the real thing.

Birth of an Island – 5 Million B.C.

Birth of an Island: Learn more

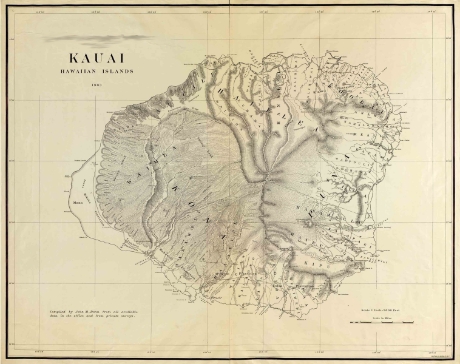

Over 5 million years ago, Kauaʻi took its place as part of an island chain. Magma spewing from a hot spot beneath the floating Pacific Tectonic Plate formed Kauaʻi as it did the other islands in the chain.

The plate, bearing Kauaʻi, moved on, as the destiny of these islands is to remain in motion, advancing in a northwesterly direction at the rate of about 3.5 inches per year while slowly eroding and declining. The tops of most of these islands no longer exist above sea level; many have subsided under the Aleutian Chain in Alaska.

First came the plants. Over millions of years, every 10,000 to 100,000 years or so, a new plant arrived, until a total of about 270 colonizing species bloomed in these islands. They arrived without the aid of people, on wings and in the bellies of birds, or they rafted here on vegetation. These 270 or so colonists evolved over millennia to become significantly different so that by the time the first Polynesians arrived, they saw those 1,300 or so flowering plants mentioned earlier.

Ancient Kauaʻi – 200 A.D. to 600 A.D.

Ancient Kauaʻi: Learn more

Imagine setting out in a double-hulled outrigger sailing canoe from the Marquesas Islands, over 2,000 miles away, and coming upon the emerald spires of Nā Pali (meaning: the cliffs) piercing the azure and cerulean skies.

That is what the early Polynesians who settled on Kauaʻi did. There is evidence of their existence dating back to as early as 200 and 600 A.D.

Near shorelines and among the valleys of the Nā Pali Coast, they grew their staple crop—kalo (or taro)—along with sweet potato, breadfruit and other plants that they brought with them in their voyaging canoes. They would use their harvest for food, clothing, shelter and medicine. They managed resources wisely and practiced masterful irrigation techniques to redirect water to rivers where they fished, planted, and harvested in season.

When they arrived, early people found what modern-day botanists estimate were 1,300 or so native flowering plant species growing in these islands. Today, many of those plants are endangered, threatened and rare.

People adapted to life in their new land, where they thrived. Hundreds of years later, in succeeding migrations, the strong, fearsome Tahitians arrived and overpowered them, establishing the Tahitian religion and culture as the basis for Hawaiian society.

Hawaiians built heiaus, or temples, to worship their pantheon. Among the most famous in all Hawaii are heiaus they built in an arc starting at the Wailua River on the East Side, ascending to the top of the highest region of Kauaʻi, Waiʻaleʻale, and down to the West Side.

They considered the entire Wailua region sacred. Royals from other islands came to Wailua to give birth to their progeny at Holoholoku, sacred birthplace of the chiefs. So special was this birthing place that it gave rise to a saying :

” Hanau ke alii I loko o Holoholoku, he alii nui hanau ke kanaka I loko o Holoholoku, he alii no hanau ke alii mawaho a‘e o Holoholoku aohe alii he kanaka ia “

” The child of a chief born in Holoholoku is a high chief; the child of a commoner born in Holoholoku is a chief; the child of a chief born outside of the borders of Holoholoku is a commoner.”

Perhaps the ancients saw the only two native mammals found in all of Hawaii—the Hawaiian Hoary Bat, or opeape, and the endangered Monk seal, ilio-holo-i-ka-uaua.

The green sea turtle, or honu, now threatened, swam in abundance. Birds and fish were plentiful.

“At least 1,000 creatures that once enlivened Hawaii’s landscape have vanished since Polynesian voyagers—and later European explorers—first set foot here…”

—Elizabeth Royte “Hawaii’s Lost World,” National Geographic

Though new faces are on the land, the bones, or iwi, of the ancients lie buried in caves and in sandy shorelines. Information about these Polynesians, who became the Hawaiians of today, continues to unfold as excavations reveal new findings.

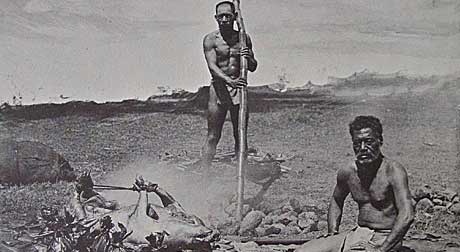

On the South Shore of Kauaʻi, for example, evidence unearthed within the past decade shows that early fishermen established temporary fishing camps there. They built heiau, or temples, to their gods, likely praying for abundance.

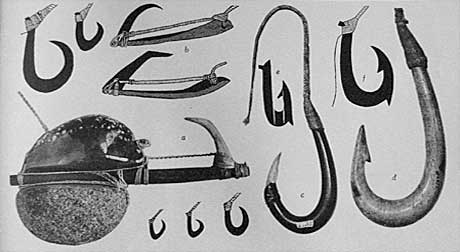

Remnants of their tools remain to help paint a picture. These early fishermen knew the best spot to find octopus and how to use a device made with a cowry shell to lure them. They knew how to fashion fish hooks from bone and cutting tools from chips of basalt flakes—which leads to an integral part of the story of Kauaʻi—the land itself.

Western Contact – 1778 A.D.

Western Contact: Learn more

hundreds of years, until 1778, people of Kauai lived on the land without further outside influence. But when Captain James Cook landed his ships Resolution and Discovery at Waimea Bay on the west coast of Kauai during that fateful year, he opened the door to the influx of westerners—missionaries, businessmen, laborers and succeeding cultures that gradually diminished the numbers of full-blooded Hawaiians.

With all these foreigners came ideas, materials and foods different to those of the native Hawaiians. With them, they also brought diseases against which the Hawaiians had no immunity and which decimated the native Hawaiian population.

A time of great change lay upon the land. Ancient kapu, or taboos, crumbled. War no longer seemed a viable option for settling larger differences.

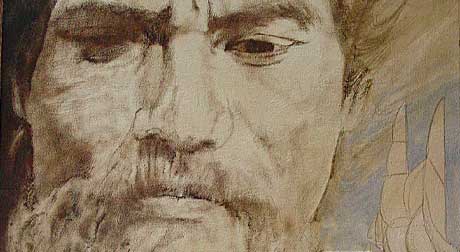

King Kaumualii, the last king of Kauai, lived during this tumultuous time.

From the moment of his birth in the sacred Wailua region ca. 1780, King Kaumualii lived a remarkable life. In what many call a wise move, he avoided the slaughter of his people in battle by ceding his kingdom to King Kamehameha the Great—the ruler of all Hawaii—who conquered all the main islands except Kauaʻi.

In return for his bloodless surrender and vowed allegiance to Kamehameha, and, upon Kamehameha’s death, to his successor and son, Liholiho, King Kaumualii kept his rank and titles.

Kaumualii was no stranger to battle. He’d had his first taste of it as a warrior when, at age 14, following the death of his father, he fought to rule his kingdom. Though Kaumualii was defeated then, within two years, his enemy was dead and Kaumualii assumed his rightful kingship.

At age 44, Kaumualii died, but not before being kidnapped and taken to Oʻahu by Liholiho, wed to one of Kamehameha’s widows—the powerful Kaahumanu—and, say some, powerfully influenced by Christianity.

Perhaps the ancients saw the only two native mammals found in all of Hawaiʻi—the Hawaiian Hoary Bat, or opeapea, and the endangered Monk seal, ilio-holo-i-ka-uaua.

The green sea turtle, or honu, now threatened, swam in abundance. Birds and fish were plentiful.

“At least 1,000 creatures that once enlivened Hawaii’s landscape have vanished since Polynesian voyagers—and later European explorers—first set foot here…”

—Elizabeth Royte

“Hawaii’s Lost World,” National Geographic

Though new faces are on the land, the bones, or iwi, of the ancients lie buried in caves and in sandy shorelines. Information about these Polynesians, who became the Hawaiians of today, continues to unfold as excavations reveal new findings.

On the South Shore of Kauaʻi, for example, evidence unearthed within the past decade shows that early fishermen established temporary fishing camps there as early as 200 to 600 A.D. They built heiaus, or temples, to their gods, likely praying for abundance.

Remnants of their tools remain to help paint a picture. These early fishermen knew the best spot to find octopus and how to use a device made with a cowry shell to lure them. They knew how to fashion fish hooks from bone and cutting tools from chips of basalt flakes—which leads to an integral part of the story of Kauaʻi—the land itself.

Missionary Era – 1800s

Missionary Era: Learn more

Missionaries sailed out of New England to convert the Hawaiians to Christianity, the first boatload of them arriving in 1820 in the Hawaiian Islands. They endured their own survival journeys—188 days sailing around Cape Horn and South America.

The first missionaries to arrive in the Hawaiian islands included Mr. Samuel Whitney and his wife, Mercy Partridge Whitney, who with Mr. Samuel Ruggles and his wife, Nancy Wells Ruggles, established the mission station at Waimea, Kauaʻi in 1820. Waimea was the capital city, located at the mouth of the Waimea River. Later companies of missionaries established missions in 1834 in Kōloa on the South Shore and Waioli on the North Shore.

As a rule, missionaries brought strict changes, enforcing kapu, or restrictions. No more nudity. Women must wear Mother Hubbards, long, loose-fitting gowns that evolved to the mu‘umu‘u chosen as daily wear by many women in Hawai‘i until this day. No more hula—a dance with sacred roots that also entertained.

Paradoxically, while they set about deconstructing a culture, missionaries were also the ones to begin to record it, creating a written language from an oral tradition. This they used to translate the Bible into Hawaiian.

Children of the missionaries, the new kama‘aina, or children of the land, set about establishing themselves in differing professions. Many became land and sugar plantation owners.

Plantation Era – 1800s to 1900s

Plantation Era: Learn more

Polynesians brought sugar cane, or ko, with them in their sailing canoes. It was a plant whose leaves they used for thatching, and to wrap fish bait.

They also used ko as a sweetener in herbal preparations and chewed on it to clean their teeth. Some reported that mashing its young vines with those of another plant—koali awa vine—and adding salt was effective in reattaching severed portions of the body.

In their wildest dreams, the Hawaiians would never have developed the plan that put the town of Kōloa, Kauaʻi on the map, brought riches to Caucasians, opened the door to waves of immigrant laborers and set the new order of the land for the century to come. Hawaiians were subsistence/sustainable agro-foresters. The newcomers—children of the missionaries and other immigrants, true to their western leanings— embraced the industrial revolution and were into agro-business before it became a buzzword.

The first successful commercial milling of sugar in all of Hawaii began in 1835 in Kōloa Town on the South Shore. It was to change the face of Kauaʻi forever, launching an entire economy, lifestyle and practice of monocropping that lasted for over a century.

Because of a dwindling native population, sugar plantation owners contracted immigrant labor elsewhere. First came the Chinese, then the Japanese, Koreans, Spanish, Germans, Puerto Ricans, Portuguese, Norwegians, and Filipinos, each bringing their own overlay of culture.

Many of these immigrants settled here, purchased land and became entrepreneurs. As a result, ethnic foods, arts, languages and traditional celebrations are all part of the rich history of Kauaʻi.

From hula to kachi-kachi dancing, from the Japanese O-Bon festival to the Taro Festival, King Kamehameha Day, Tahiti Fete and more, Kauaʻi enjoys a proud multicultural heritage.

Monarchy to Statehood and Beyond – 1900s to 2000s

Monarchy and Beyond: Learn more

A number of Caucasian businessmen, seeking to protect their economic interests and backed by U.S. troops, illegally overthrew Hawaii’s last reigning monarch, Queen Liliuokalani, in 1893. In 1900, Hawaii became a Territory of the United States, and Hawaii was allowed a delegate to the U.S. Congress.

Hawaii is the only state within the U.S. that had a monarchy—and had a royal serve in the U.S. Congress. That royal was Prince Jonah Kuhio Kalanianaole, a Kauaʻi native who was the grandson of the last king of Kauaʻi, King Kaumualii. He was born in a grass hut near a beach in the area now known as Poʻipu along Kauaʻi’s South Shore.

Prince Kuhio witnessed the overthrow of Queen Liliuokalani, was found guilty of treason and was made a political prisoner for a year. Later, he became Hawaii’s delegate from the Territory to the U.S. Congress, serving for 19 consecutive years.

Sugar put Kauaʻi on the map economically and was still a going concern during Prince Kuhio’s lifetime, but Kauaʻi also developed a pineapple industry on two sides of the island. Kauaʻi Fruit and Land Co. operated between 1906 and 1965 in Lawai, building the now-defunct Lawai Cannery.

Hawaiian Canneries Co., Ltd. opened in Kapaʻa on the site where Pono Kai Resort now stands. The cannery closed in 1962.

As the sugar and pineapple industries first rose and then declined, tourism emerged as the new industry driving Kauaʻi’s economy. From 668 visitors to Kauaʻi in 1927, the numbers rose to the point where new hotels began to spring up as quickly as sugar cane. Well before the new Millennium, tourism was solidly in place throughout the state as the number one source of revenue.

Many people throughout Hawaii believed that statehood would further protect their interests. In March 1959, Hawaii became the 50th State, with 10,000 people gathering at Burns Field on the west side of Kauaʻi to celebrate with a bonfire.

The force of nature has always played an important role in the story of Kauaʻi. Mother Nature gives and takes. In 1959, Hurricane Dot damaged crops and buildings.

In 1982, Hurricane ‘Iwa struck and 10 years later, Hurricane Iniki. The President declared Kauaʻi a disaster area after Hurricane Iniki, and were once the buildings had roofs, all that could be seen were blue tarpaulins stretched across housetops.

As both the past and the future of Kauaʻi continue to unfold—due to surfacing information and inevitability, respectively, the Kauaʻi Historical Society remains a constant. In its role of caretaking information, documents, videos, and photographs that tell the many stories of Kauaʻi’s history, the Society is meeting its challenge—bringing history to life.